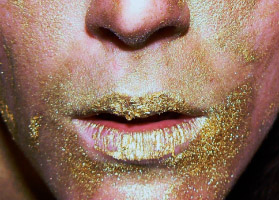

Womb Tide - Carla Lever, South Africa

Body Play: Small Thoughts on a Growing South African Physical Theatre Tradition

It’s not unusual for the creative process to be referred to in terms of pregnancy, generally by disgruntled would-be parents with the creative equivalent of swollen ankles and a bad back. This aside, it is a particularly apt metaphor when it comes to describing the burgeoning physical theatre tradition that’s currently growing in strength and influence in Cape Town.

Pregnancy is, of course, about new beginnings and growth, but it is also about using the body as a holder of life and, at another level, story. The body becomes a carrier of much more than just a physical entity and the narrative development is quite apparent to anyone who chooses – and knows how – to read it.

Cape Town’s Baxter Theatre recently saw a run of the curiously-titled Womb Tide – a beautiful piece of work from the exciting local physical theatre company From the Hip: Khulumakhale (FTH:K). FTH:K is the company who brought Pictures of You, Gumbo and, most recently, the Afro-Gothic Quack to South African audiences. The company has a progressive ethos of inclusion – it is fully integrated between Deaf[1] and hearing performers, with a strong education wing ensuring their up-and-coming talent is properly developed and channeled – and a history of producing excellent, innovative works that constantly push the bounds of South African physical theatre.

Adapted from a short story by Lara Foot, Womb Tide traces one couple’s story from the beautiful agonies of courtship to the very different kind of agony of childlessness. It’s a story imbued in equal measures with deep pain and deep joy. It’s also a very South African story, touching on the hotbed of racial prejudices and social inequalities that are still, sadly, pertinent in a post-Apartheid context as a couple, desperate for a child of their own, adopt what appears to be a homeless street orphan…or is he?

Womb Tide deals with the human side of social issues, the relationship between the colder outer world and the unique inner realms we create as reactions to, or fortresses against, that world. It’s a love story – between partners, between parents, between families. We meet hugely sympathetic, yet flawed, characters. The introduction of a puppet as the central figure around whose presence much of the drama unfolds adds another magical layer to the compelling visual complexity of the production. Whilst there are many stylistic and superficial plot similarities to FTH:K’s previous production Pictures of You (a couple’s relationship suffers under the weight of a violent attack on the life they have made for themselves), the stories stand on their own as unique expressions.

Womb Tide is, for several reasons, captivating and important theatre. It has interesting things to say about parenthood and identity as well as normativity – both physical and social – in a South African context. Not only this, but it says them in creative ways – not solely through the mouth (though inarticulate murmurs from the characters certainly convey much emotion throughout), but through the body, which is the primary carrier of the narrative and emotion.

The fact that Womb Tide is physical theatre with only the barest hint of recognizable words only heightens the characters’ tangible sense of distress and helplessness at the limits of their bodies. Words are justly celebrated vessels for conveying emotion. At times though, some things are most eloquently expressed without them. The most gut-wrenching moments in the play for me were the ones communicated in a single gesture or look.

Far from being solely an ‘imported’ Western form, physical theatre has strong resonance in an African performative context. Ritual traditions of storytelling through dance and mime hold narrative as something told through the body. Certainly, there is a distinction to be made between traditional African dance forms and a Western theatre tradition, but the base principle remains: the body as site of story as opposed to the mouth.

South Africa has, of course, a peculiar anxiety around body identity. Coming from a fraught history of seeing physicality as a (potentially damning) narrative determinant of one’s life story, the body has picked up such static buzz of meaning and taboo that it has become an extreme site of anxiety, a story in itself. Against this backdrop, I think physical theatre picks up an added resonance – and deserves critical and popular attention alike. Festivals like “Out the Box” (an annual festival of puppetry and physical performance) and individual companies like FTH:K and Magnet Theatre are making great headway in developing (predominantly) physical works of quality – the Magnet Theatre company is particularly committed to a touring program that brings its work to communities often marginalized by a combination of location, economic circumstance or language. (Incidentally, I have watched a Magnet Theatre performance where I have felt entirely sidelined both linguistically and culturally – when narrative is used it is in isiXhosa – but have been able to connect with the performance on a non-linguistic level to such an extent that I left convinced that I had experienced one of my theatre highlights of the year)

With this history in mind, I believe that in South Africa – a country of so many different languages, so many different stories, and so many different bodies/abilities – physical theatre is a form that really deserves to be explored. The focus on the body as site of anxiety helps to transcend the superficial differences between race, culture and language and opens us into a new way of communicating – and, as audience members, experiencing. Indeed, because words do not automatically spell out the plot, the audience carries the responsibility of actively creating meaning in a way that more standard theatre forms do not require, or even allow. It may – as the African proverb goes – take a village to raise a child, but in physical theatre, it takes an audience to raise a narrative.

Perhaps physical performances are often so successful (artistically, if not financially) because they lend themselves to cutting across demographics. Language barriers fall away (though cultural barriers are of course much trickier to navigate). It is often when dealing with the vocabulary of the body that performers are at their most eloquent. Not every actor is a natural wordsmith and lines often have to be assimilated – with varying degrees of success – before they can be comfortably delivered, but much physical theatre is devised within the company – born from a direct marriage between body and story and an authentic expression of each performer’s understanding and feeling of the story’s shape.

If we look to a broader scale, though, nowhere has the concept of physical performance been honed and elevated with such successful cross-cultural mass appeal as on the sports field. When it comes to visual spectacle, navigating progressive power shifts, audience investment in narrative arc and catharsis, sport as mass physical entertainment has been successful in a way that theatre can only dream of – stadiums are filled to capacity even as theatres sit empty. The amphitheatre has given way to the coliseum – and South Africans certainly do not hesitate to collectively worship its heroes. Sporting events have undoubtedly moved more and more in a performance direction – one only has to look to the evolution of the five day cricket test, through one day international and, finally, 20/20 (complete with scantily clad dancers and backing tracks for boundaries and wickets) to see this. In the same manner, the Americans have perhaps always understood the link between sport and performance, with live music, cheerleaders and even pyrotechnics having been a part of their mass sporting culture long before they were embraced by the rest of the world.

It is interesting to note that, whilst no-one questions the unifying power of sport, the centrality to a country’s culture, the personal and collective catharsis and development potential that it provides, theatre remains suspiciously sidelined, physical theatre even more so than its mainstream standard textual counterpart. Perhaps artists, with a dramatic shudder at the thought of mass commercial appeal, would have it no other way. Then again, perhaps producers, with an anxious glance at empty auditoriums and bank accounts, might give some thought to exploring the psychology around it.

Although clashing cast booking schedules mean that there are no immediate plans to re-stage Womb Tide, FTH:K company members will be performing two new pieces in South Africa for 2011: Kardiavale – intriguingly billed as ‘cabaret clown noir’ – and Benchmarks.

© Carla Lever. All rights reserved.