Somewhere Over the Rainbow (Nation)

by Penny Youngleson ( South Africa )

writing to the “New” South Africa, about the “New South Africa”...in South Africa.

In conversation Spalding Gray wondered:

Could I stop acting, and what was it I actually did when I acted? Was I, in fact, acting all the time, and was my acting in the theatre the surface showing of that? Was my theatre acting a confession of my constant state of feeling my life as an act? Now there was the new space between the timeless poetic me (the me in quotes, the self as poem) and the real-time self in the world (the time-bound, mortal self; the self as prose). The ongoing ‘play’ became a play about theatrical transcendence.

(Callens 2004: 118 – 119)[1]

Gray’s performance was a theatre of identity, of a personal politics premised on the unearthing of stories that had hitherto seemed too lacking in significance to be told to paying strangers.

This was highlighted for me during January 2008 when I was involved in the Infecting the City Festival in Cape Town, South Africa. Whilst conducting ethnographic interviews with volunteers in the midst of the xenophobic attacks in South Africa (the theme that year was Home Affairs) I was struck by the number of white women in their mid to early forties who had volunteered hours of their time to help the victims of civic violence reconstitute their lives. Whilst this sacrifice was admirable (and I am, in no way, attempting to negate the importance of their contribution or to question the conscious motives of their involvement) their fervor felt almost too violent. Their sense of injustice and betrayal too personal. Their interest in the victims could almost be read as self-pivoting. Many of these women had been active in protesting against Apartheid in their twenties (during the late 1980s to early 1990s State of Emergency in this country) – and felt a renewed sense of importance, and identity, to have found a cause to “fight” for again. And it was because of their zeal that I recognized that this “homelessness” or invisibility that I felt was not something that was exclusive to me. It was a recurring void that I observed in many of my acquaintances and colleagues.

White women have necessarily occupied an uneasy space, falling somewhere between the phallogocentricity [3] of Cartesian subjectivity and the iconographic other of “Western” Imperialism. (West, M. 2009:4)[4]

This inquiry inevitably took my writing into Whiteness Studies, an area of research dedicated to understanding the social construction of epidermal ethnicities (with those categorised as “white” being a particular focus) and the resulting effect these constructions have on interactions of status, socio-political dynamics and wealth distribution – amongst others. Because of South Africa’s particular history, Whiteness Studies in this country is an extremely rich site for both academic rhetoric and discourse as well as creative prose.

Autobiography, or ‘autoperformance’ (Freeman 2007: 95)[5], does more than provide artists with the opportunity to make themselves subjects to be seen by spectators; it allows them to see themselves in the process of being seen. Lacan described a state wherein ‘the visible me is determined by the look that is outside me’ (Lacan 1977: 49)[6]. A questioning of self through self’s construction, the self as subject does not, we see, amount to the self as given. Autoperformative identity is under constant challenge from selective memory and an oscillation between self-mirroring, self-questioning and self-inventing – and there are distinctions between the terms “identity”, “person”, “self” and “autobiography”. Barthes writes about this as the ‘self who writes, the self who was and the self who is’ (Barthes 1977: 56)[7]. Likewise, Peter Brook asserts that ‘in everyday life “if” is a fiction… In everyday life “if” is an evasion; in the theatre “if” is the truth’ (Brook 1968: 157).

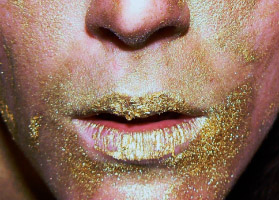

Archival photo from Expectant, a one-woman show discussing themes of gendered guilt and ethnic representation – with specific reference to “White Gilt”[8]

Another “problem” inherent in the writing I was doing was the method of reconciling the practicalities of gender, the female, femininity and my understanding of what it meant to be a woman (and a white woman in South Africa) with the liberal philosophies and theories I purported to subscribe to. In this vein the idea of the inscription of gender on the body became more and more important in exploring what it was to write for and about my country.

Sartre associates the feminine with the ambiguous hybridity of slime:

I want to let go of the slimy and it sticks to me, it draws me, it sucks at me. Its mode of being is neither the reassuring inertia of the solid nor a dynamism like that in water which is exhausted in feeling from me. It is a soft, yielding action, a moist and feminine sucking, it lives obscurely under my fingers, and I sense it like a dizziness; it draws me to it as the bottom of a precipice might draw me

(Sartre 1956: 609)[9].

Twenty-three years later, Carolee Schneemann reiterates the unfortunate truism that this point posits (and her frustration with the indoctrination and engendered notion of the female understanding of the self in performance and everyday life):

The living beast of their flesh embarrasses them; they are trained to shame… blood, mucus, juices, odours of their flesh fill them with fear. They have some abstracted wish for pristine, immaculate sex… cardboard soaked in perfume.

(Schneemann 1979: 58)[10].

There is an intricacy and an intimacy to the female form (particularly in this country) that remains undetected and undiscussed. And it is through readings of Ruth Frankenberg’s identification of a “masquerade” (influenced by Joan Riviere’s well-known psychoanalytic essay ‘Womanliness as Masquerade’ (1929)) and Georgina Horrell’s work ‘A Whiter Shade of Pale’ (speaking to femininity as a masquerade in white women’s writing in South Africa) that as practitioners we can start to unravel the points of intersection, through a Butlerian lens, of the “performance” of Whiteness and gender.

As South Africans, we are subject to external factors including, but not exclusive to, globalization, free trade, post-colonial expression and current social philosophy, gender, race, occupation, social rituals, lifestyle, language, religious faith, economic class, political beliefs, educational background, family relationships and our environment. ‘We can never see reality just as it is... Any act of seeing is an interpretation: a process of giving meaning to what we see’ (Holloway, Kane, Roos and Titlestad 1999:169)[11]. We often define ourselves in relation to others, with a logical legacy of “othering”. I hope that by continuing to write back to these topics we can begin to demystify some of the haze surrounding our understanding of our selves and people who have been classified as “White like Me”[12]. As a female. As a South African. As a white, English-speaking, female, South African. As all of these facets and their associated fabrications. There is no end to the construction that informs and deforms me. And there is no more exciting time to be writing about it.

- Callens, J (ed.) 2004. The Wooster Group and its Traditions. Brussels: Peter Lang

- Barthes, R. 1984. Camera Lucida. London: Fontana Paperbacks

- A concept that gained currency in l’écriture feminine, associated with French Feminists, namely Hélène Cixous, Julia Kristeva and Luce Irigaray, to denote the centrality of the phallus and logos in the Lacanian symbolic order.

- West, M. 2009. White Women writing White. Claremont: David Philip Publishers

- Freeman, J. 2007. new performance/new writing. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lacan, J. 1977. The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis. Alan Sheridan (trans.) London: Hogarth Press.

- Brook, P. 1968. The Empty Space. London: Macgibbon & Kee

- White Gilt” is a term used by Penelope Youngleson in reference to the thin layer of power and privilege (akin to epidermal ethnicity) that cleaves the wealthy liberal and allows a position of patronage. In Expectant Youngleson covered herself in gold leaf and gold powder, creating a new “ethnicity” for white women in the “New” South Africa.

- Sartre, J. 1956. Being and Nothingness: an essay on Phenomenological Ontology. Translated by Hazel E. Barnes. New York: Philosophical Library.

- Schnemann, C. 1979. More Than Meat Joy: Complete Performance Works and Selected Writings. Bruce McPherson (Ed). New York: Documentext.

- Holloway. M, Kane. G, Roos, R & Titlestad. M. 1999. Selves and Others: Exploring Language and Identity. Cape Town: Oxford University Press

-

Brett Murray. Standard Bank Young Artist Awardee. 2002

by Penny Youngleson, South Africa